January 30, 2016

Got a brand problem? Put a bird on it.

A Special Hell for Designers Like Me (Part 2)

This post is going to go to a dark place, so let’s start out with a little fun. Here’s that video clip from Portlandia where Bryce Shivers and Lisa Eversman transform junk into treasure by putting birds on things.

Cracks me up. Anyway, it’ll make more sense later. Now then, on to hell...

My first post about designer hell showed how the tricks of the design trade have a fundamental potential for deception. On the surface, the degree of sin inherent in these illusions is debatable. To really dance with the devil you have to ask questions. Let’s start with this one:

Why weren’t there any logos on the thousands of RVs that were sent to the victims of hurricane Katrina?

I was on a photoshoot in Indiana when a southbound train crossed my path, packed with generic RVs. I naively assumed it represented an act of goodwill. I asked my co-workers if they knew which manufacturer was making the donation. They let me in on the secret.

“Donation? Why do you think there isn’t a single logo on those RVs?”

Strange, isn’t it? You might guess that an RV company would welcome the publicity that comes from helping fellow Americans affected by a disaster. The debranding wasn’t an act of humility or an oversight. No, it was denial, an intentional disassociation with their involvement in the project. Here’s why…

FEMA was desperate to buy RVs. They were essentially writing blank checks. Any company that could slap together 4 walls on wheels was probably lining up to pack their product on those trains. These RVs were lower quality than average, a scary thought when you consider the low standards of the RV industry.

In fact, they were so cheaply made that there was concern that simply transporting them from Indiana to Louisiana could shake the mobile homes to pieces. They would be lucky to make it to their destination with cabinets still attached to walls.

You don’t put your logo on the side of something like that. You hope nobody asks who made it.

My eyes were opened. There in that Indiana photo studio I took a hard look at my client’s RV through the lens of my camera. A sticker of a cartoon bird smiled back at me. If I removed the decals I would have no way of distinguishing this white box from the ones on that train.

(I guess I should write a disclaimer before this gets worse. I don’t know if my client’s RVs were part of the shipment to the Gulf Coast. The people I worked with were nice people and I don’t have any evidence they are guilty of anything other than being indistinguishable from every other RV manufacturer. My goal isn’t to disparage them, they just happen to be my connection to the bigger story.)

The RVs on those trains held together. They made it to Louisiana intact, but there was another problem. The incentive to rush the building of the RVs tempted the manufacturers to skip their normal safety processes. Formaldehyde is not an uncommon byproduct of the manufacturing process, but without care the carcinogen levels become deadly.

The RVs that were intended to rescue people ended up poisoning them.

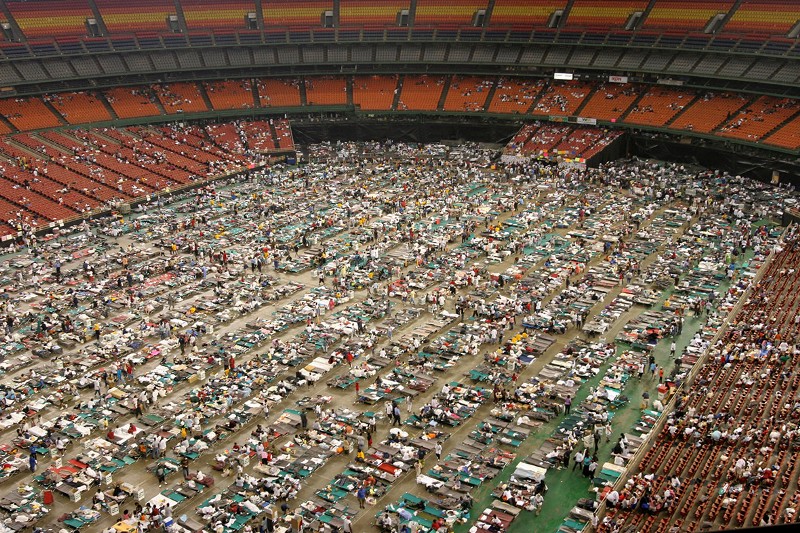

People got sick. Lawsuits were filed. The RVs needed to be quarantined. Thousands of empty RVs were parked in fields miles from where newly homeless people slept in crowded shelters.

When it became apparent that the RVs were uninhabitable, FEMA had a new disaster to deal with. How do you make thousands of toxic RVs disappear?

Answer: you slap a sticker on the window and have a blowout sale.

Do you know what the generic sticker in the window said? No, it wasn’t a cartoon mascot, a hand-stenciled bird, or a glossy logo. It was the most understated tagline any marketer has ever conceived of. It said,

“Not to be used for housing.”

A mobile home with a “not to be used for housing” sticker. Maybe if you put it upside-down people won’t read it.

FEMA successfully auctioned off the toxic RVs. The “not to be used for housing” stickers were quietly removed and the mobile death houses spread across the country. The resellers, if they even gave it a second thought, probably comforted themselves with the fact that formaldehyde levels drop with each passing year. If you wait long enough, tragedies fade into the background.

A documentary by Nick Shapiro shows how in nearly any RV park in America you can find someone living in a toxic FEMA RV, oblivious to the history or risks to their health.

Where did humanity fail in this story?

It seems obvious to blame FEMA, RV manufacturers, and the RV resellers. That’s too easy. These groups are made up of individuals. Each person in the chain, from the assembly line worker to the auctioneer contributed to the disaster. Instead of asking questions they pointed to the excuse that has become a national slogan:

“That’s not my job.”

If enough people share that mantra, terrible things happen. Cataclysms are rarely masterminded conspiracies, they tend to be cascading apocalypses of apathy.

This is why I only half joke about a special hell for designers. It seems like our work exists at a safe distance from the moral questions, but we are one of the many voices that can stop the train before it leaves the station loaded with toxic cargo. If we don’t ask tough questions, we are just zombies, another lifeless worker, led by brainless leaders, building worthless products.

I, obviously, have some guilt about my tiny contribution to this tragedy. The reason I can’t shake it is because I know I could so easily fall into this trap again. Heck, I was a designer for a company not much better than the RV criminals when I wrote Art of the Living Dead. Instead of questioning the integrity of the products I am helping to sell, I too often am happy to just “put birds on things.”

As designers we are eager to believe the myths we create. When we learn our client has Amish people on staff, our instinct is to add bullet points about “Amish Craftsmanship” to our brochures, complete with a stock photo of a bearded man wearing a straw hat to assist the fiction we are creating. Guilty.

I have created many logos in my career. I could walk away from these logos and point at the skill of my designs and say, “I did my job.” The reality is that my designs aren’t artifacts of great brands. They are careful illusions, little lies that distort the truth of the companies they represent. Guilty again.

I often write critically about branding. At its best, a brand is a representation of integrity. We proudly mark the things we make and stand behind our products. Brands rarely achieve this ideal, however. Instead, companies copy their competitors pushing industries toward commodification. When branding is removed from a product, whether it is an RV or a Chevy, the artifacts of integrity must still remain. If they don’t, branding isn’t a helpful tool, but a decoy that pollutes our world with deception.

Designers love branding projects because it is a chance to reshape perceptions. But if you have to hire an advertising agency to tell you what makes your company different, your problems won’t go away with the arrival of a new logo. Sorry.

Even if we did have the integrity to notice the lies we spin, or the harmful lack of quality in our client’s products, would we have the courage to do something about it? And how would you go about it? Do you risk your job by asking dangerous questions? Do you walk away from a paycheck? These are the tough questions that I hope you wrestle with. That is our job.

So am I going to hell? The thing about salvation is it ultimately isn’t up to us. A higher power has the final say. All we can do is try our best to be honest in our work. Perhaps even for a flawed designer like myself, damnation can be prevented. Stay creative.

Previous: A Special Hell for Designers Like Me